Diane Cho, headshot.

Interior (2017), Center Stage, Baltimore.

Theater stage (2012), Everyman Theatre, Baltimore. photo / Alan Gilbert

Matisse Gallery (2022), Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore.

Projects

American Visionary Art Museum (2008)

Jim Rouse Visionary Center (2008), exterior, Baltimore. photo / Alain Jaramillo

Jim Rouse Visionary Center (2008), entryway, Baltimore. photo / Alain Jaramillo

Jim Rouse Visionary Center (2008), recycled glass wall, Baltimore. photo / Alain Jaramillo

Jim Rouse Visionary Center (2008), balcony gallery, Baltimore. photo / Alain Jaramillo

Jim Rouse Visionary Center (2008), recycled whiskey barrels stave wall, Baltimore. photo / Alain Jaramillo

Everyman Theatre (2012)

Exterior pre-renovation (2008), Baltimore. photo / Alan Gilbert

Exterior, Baltimore. photo / Alan Gilbert

Lobby, Baltimore. photo / Alan Gilbert

Theatre stage, Baltimore. photo / Alan Gilbert

Second floor lobby, Baltimore. photo / Alan Gilbert

Open Works (2017)

AIABaltimore Excellence In Design Award Winner (2017), Cho Benn Holback + Associates, a Quinn Evans company, Baltimore.

Cho Benn Holback + Associates, a Quinn Evans company, exterior view, 34,000-square-foot building, Baltimore. photo / Karl Connolly

Cho Benn Holback + Associates, a Quinn Evans company, interior view, lobby, Baltimore. photo / Karl Connolly

Cho Benn Holback + Associates, a Quinn Evans company, interior view, CNC Studio, Baltimore. photo / Karl Connolly

Cho Benn Holback + Associates, a Quinn Evans company, exterior view, porch, Baltimore. photo / Karl Connolly

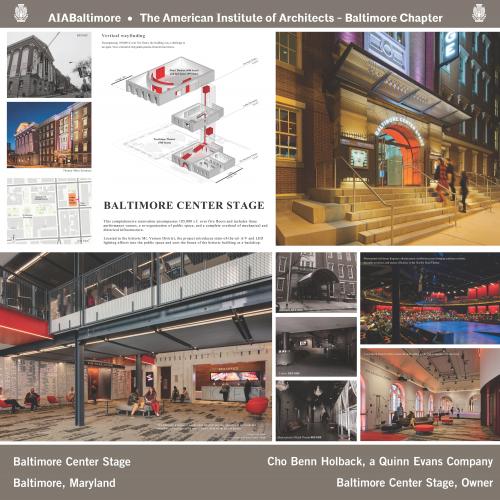

Baltimore Center Stage (2017)

AIABaltimore Excellence In Design Award Winner (2017), Cho Benn Holback + Associates, a Quinn Evans company, Baltimore.

Cho Benn Holback + Associates, a Quinn Evans company, exterior view, 105,000 square feet, Baltimore. photo / Karl Connolly

Cho Benn Holback + Associates, a Quinn Evans company, interior view, entry arch, Baltimore. photo / Karl Connolly

Cho Benn Holback + Associates, a Quinn Evans company, interior view, Baltimore. photo / Karl Connolly

Cho Benn Holback + Associates, a Quinn Evans company, interior view, main lobby, Baltimore. photo / Karl Connolly

Cho Benn Holback + Associates, a Quinn Evans company, interior view, Head Theater lobby and bar, Baltimore. photo / Karl Connolly

Cho Benn Holback + Associates, a Quinn Evans company, interior view, Head Theater, Baltimore. photo / Karl Connolly

Baltimore Museum of Art Renovation (2022)

Study Room, Nancy Dorman and Stanley Mazaroff Center for the Study of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs (2022), 7,000 square feet, Baltimore, courtesy of Quinn Evans.

Quinn Evans Architects, gallery, Center for Prints, Drawings, and Photographs (2022), Baltimore, courtesy of Quinn Evans.

Quinn Evans Architects, Center for Prints, Drawings and Photographs (2022) and Ruth R. Marder Center for Matisse Studies (2022), Baltimore, courtesy of Quinn Evans.

Quinn Evans Architects, gallery, Center for Matisse Studies (2022), Baltimore, courtesy of Quinn Evans.

Quinn Evans Architects, Study Room, Center for Matisse Studies (2022), Baltimore, courtesy of Quinn Evans.

Color: Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Distinctio, eveniet?